Nonsense.

Telling a 4th grader that in a decade they will need to use multiplication someday when they are buying apples in the grocery store, trying to convince a middle school student that finding the main idea of a non-fiction passage will be vital in their future career, or asking a high-school sophomore to know the function of a mitochondria because someday they might be a doctor are all great ways to get children to drool on their desks out of boredom rather than actually engaging in learning.

If you have spent time around any children of school age, you know that this will not convince them that the content they are learning is relevant. The frontal lobe of our brain, which allows us to understand the consequences of our actions, is not fully developed until our mid-twenties.

In schools, we need something more effective than, "Trust me. I'm an adult."

If we want school to be relevant to what's going on outside our school walls, we actually need students to get involved in using learning to solve problems outside our school walls.

If we want school to be relevant, make it relevant. Don't pretend it's relevant and try and sell that to kids.

|

| Students working on building aquaponics units out of recycled materials to help those in regions with drought. |

Problem-based learning, when combined with a focus on improving students' local and global communities, creates a dynamic environment in which students don't have to wonder why they are learning. They know they need to learn in order to make their world a better place.

Using learning to make the world a better place is exactly what education should be about. Many of our school mission statements include language about creating contributing members of society and good citizens.

Early in my career, I remember helping 5th graders understand fractions by planning and cooking a Thanksgiving dinner for a family in need. More recently my 4th and 5th grade students have designed and facilitated a global video learning exchange that helped children with limited resources learn with math manipulatives. They collaborated on a global garden project where students exchanged techniques they learned to grow food. When they met children in a rural Kenyan village that couldn't go to school because the community bridge was dangerous, my students used the learning in their science class to design a new bridge that was built with funds they raised. Last year, after hearing about the drought and famine affecting children in Malawi, my 5th grade students designed aquaponics units out of recycled materials that grew food with 90% less water than traditional farming.

|

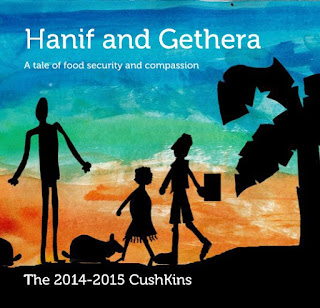

| Book written and published by Beth Heidemann's students |

My students don't ask me why they are learning. The relevance is obvious.

If you teach younger students, know that children are never too young to change the world.

When Beth Heidemann's kindergarten students in Maine learned that the friends they met in the Kibera Slum of Nairobi faced food insecurity issues that mirrored some of the issues in their rural town, they wrote a fairy tale. It was set in Kenya and described children overcoming problems due to lack of food. They published the book and used the proceeds to send funds to both their local food pantry and their friends in Kibera.

It is vital that this relevance extends to all subject areas, including the arts. The arts allow children to learn to perceive beauty in the world. More importantly, though, the arts allow us to emotionally connect with each other. They allow us to develop empathy and find our shared humanity.

Mairi Cooper's orchestra students have used the design process to innovate new ways to use music as a tool for social good. Using "pop-up concerts," they have found ways to bring the beauty of orchestra music to people in locations that otherwise would not have access, including homeless shelters and children's hospitals.

Students in any subject area or grade level can find true relevance in their learning if we give them the autonomy, resources, and support.

|

| Mairi Cooper's students performing at a center for the blind. Picture credit: Twitter.com/patoy2015 |

If we hold dear to our traditions and tell children that school is relevant, while at the same time our actions show them that what we really care about are arbitrary numbers written at the top of Friday's test, state assessment scores, or class rankings, our students will see right through us.

While mindset shifts can be scary and take time to fully develop, here are some ways to get started:

- Understand that the learning in your classroom belongs to the learners and not to the teacher. Make small changes to move from a coercive environment to a learning environment where inspiration is used to motivate. Give your students as much autonomy and choice over classroom rules, curriculum, and application of learning as you can.

- Start with local issues. Help students begin thinking about ways their learning can be used to make their community better. Over time, help them understand that they are also part of a global community.

- Use the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as the basis for connecting required content to initiatives to make the world a better place. TeachSDGs.org is a great tool for helping students see the context for the content they learn.

- You can't change the world if you don't know much about it. Use free videoconferencing tools to allow your students to learn with other students in distant locations.

- To learn more about how to shift toward a Project/Problem Based Learning environment, start with Ginger Lewman's book "Lessons for LifePractice Learning."